IIT Bombay study shows how TB bacteria shield themselves from antibiotics, stay alive longer

By IANS | Updated: December 3, 2025 13:05 IST2025-12-03T13:00:26+5:302025-12-03T13:05:14+5:30

New Delhi, Dec 3 The bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes the world’s most infectious disease Tuberculosis (TB), can ...

IIT Bombay study shows how TB bacteria shield themselves from antibiotics, stay alive longer

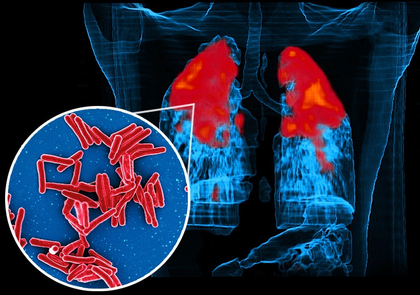

New Delhi, Dec 3 The bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes the world’s most infectious disease Tuberculosis (TB), can survive antibiotic treatment and live longer by changing their outer fat coating, according to a new study led by researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay on Wednesday.

Even with effective antibiotics and widespread vaccination campaigns, TB continues to take lives.

Globally, 10.7 million people developed TB and 1.23 million died from the disease in 2024, while India carries one of the highest burdens -- over 2.71 million cases in 2024.

In the study, published in the Chemical Science journal, the researchers showed that the key to the bacteria's drug tolerance lies in their membranes -- complex barriers made mostly of fats, or lipids that protect the cell.

The team grew the bacteria under two conditions: an active phase, when the bacteria were dividing rapidly as they do in an active infection, and a late stage mimicking dormancy, as seen in latent infections.

When they exposed the bacteria to four common TB drugs: rifabutin, moxifloxacin, amikacin, and clarithromycin, the team found that the concentration of drugs needed to stop 50 per cent of bacterial growth was two to 10 times higher in dormant bacteria than in active ones.

In other words, “the same drug that worked well in the early stage of the disease would now be needed at a much higher concentration to kill the dormant/persistent TB cells. This change was not caused by genetic mutations, which usually explain antibiotic resistance,” said Prof. Shobhna Kapoor from the Department of Chemistry, IIT-B.

Lack of mutations associated with antibiotic resistance in the bacteria confirmed that the reduced drug sensitivity could be linked to the bacteria’s dormant state and most likely their membrane coats rather than genetic changes.

Further, the team identified more than 270 distinct lipid molecules in the bacterial membranes, which showed clear differences between active and dormant cells.

While the active bacteria had loose, fluid membranes, the dormant ones had rigid, tightly ordered structures, indicating its defence mechanism.

“People have studied TB from the protein point of view for decades,” said Kapoor.

“But lipids were long seen as passive components. We now know they actively help the bacteria survive and resist drugs,” she added.

Next, the team found that the antibiotic rifabutin could easily enter active cells but barely crossed the outer membrane of dormant ones.

“The rigid outer layer becomes the main barrier. It is the bacterium’s first and strongest line of defence,” explained Kapoor.

If the outer membrane blocks antibiotics, weakening it could make the drugs work better.

“Even old drugs can work better if combined with a molecule that loosens the outer membrane,” said Kapoor, noting that the approach makes bacteria sensitive to the drugs again without giving them a chance to develop permanent resistance.

Disclaimer: This post has been auto-published from an agency feed without any modifications to the text and has not been reviewed by an editor

Open in app